I was casually surfing YouTube last night, hitting command+T on a bunch of thumbnails in the sidebar. One of them was this video, where Warren Buffett says this about Charlie Munger:

Charlie always thought I did too many things. He thought if we did about five things in our lifetime, we’d end up doing better than if we did fifty…and that we never concentrated enough.

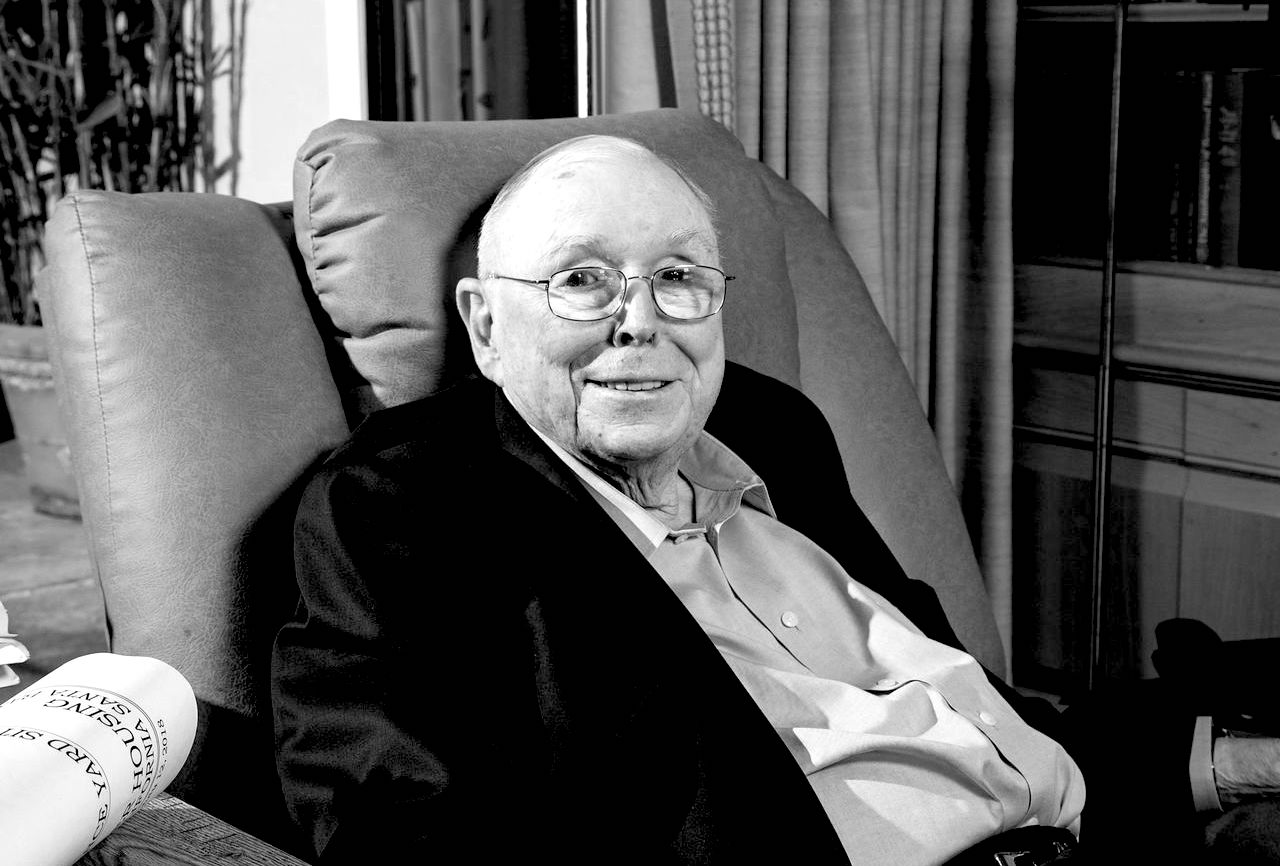

This line sent me down a Charlie Munger rabbit hole, something I’ve been putting off so I could give it my full attention because I know just how much I have to learn from him and how much the personal philosophy I’ve developed is in line with his. I was saving the moment, but finally it sprung on me and I could no longer resist.

I’ve heard a bunch from smart people I learn from about how brilliant Charlie was, hearing direct quotes around the idea of high-leverage selection, patience as a strategy for cultivating opportunity, creating the time and space to focus by having few priorities at once, and more.

Here are a few of the mental models that I enjoyed the most from my first trip down the Munger rabbit hole:

Constant learning…that feels fun. Charlie is almost never not reading or in conversation for the sake of learning. A lot of people try to emulate this by reading exactly the same stuff he’s read, and to digest as much text as possible. If this sounds forceful, it’s because it is. But not for Charlie. He made it look effortless, because I think it was. He was intrisincally motivated to constantly learn about the things he was learning. It’s not like he learned about biology or astrophysics. He had specific information sources that fed him a constant diet of learning in that particular niche of his. He was able to sustain decades of deep learning because it didn’t feel like work to him. That was his advantage.

Being deliberate. He kept the horizon clear so that he could clearly detect signal when it arises, he was assertive when it came to declining new commitments. He said no to tons of investments that turned out to be good, so that he was able to deploy capital for the investments that turned out to be great. This naturally meant that the few things he did commit to, he committed to with huge positions. But his high-leverage decisions were enabled by deliberately doing less things.

Patience I think this is his top virtue; everything is downstream of this. Without patience, he would have committed hastily to investments that seemed good, which would have tied his capital to weak positions, and would have forced him to sell as soon as a better investment came around. This reactive state is all too common for not just 90% of investors, but for 99% of humans. Instead, Charlie flexed his ability to stay put, like a lion waiting for the perfect moment to pounce. Because of his extensive patience, when amazing opportunities arose, he was well positioned to not just go for them, but to go all-in on them since he saved his capital for exactly this moment.

Leave a Reply